Großes Festspielhaus, Salzburg (Detail).

© Thomas Prochazka

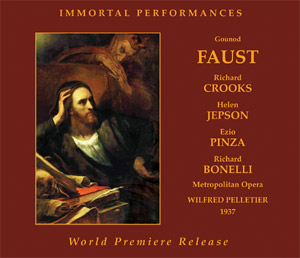

[EN] Immortal Performances:

“Faust” (Metropolitan Opera, 1937)

Von Thomas Prochazka

II.

In 1996, Richard Caniell had already taken on the challenge to make the Metropolitan Opera’s broadcast from 6 April 1940 available to opera devotees around the world. The 1940 broadcast had been recorded on a tour of the New York opera company in Boston, and was available on the Naxos label (and others) for quite some time.

Both broadcasts feature Helen Jepson, an American lyric soprano, as Marguerite, Richard Crooks as Faust, and Ezio Pinza as Méphistophélès, with Wilfred Pelletier on the rostrum. In the 1940 recording, Leonard Warren sang the role of Valentin while in 1937 Richard Bonelli was a great success with the Met audience.

III.

In a blog post from January 2019, Conrad L. Osborne, one of the leading American opera critics, expressed his view that Faust, the operatic masterpiece, has gone MIA — missing in action. After World War II, there have been many attempts to connect with its great vocal tradition but all recent undertakings I have knowledge of don’t do the work justice.

Of course, great singers of all times recorded arias from Faust. However, comparing the Now and Then, any opera devotee interested in operatic voices will have to concede that recent recordings are no longer at par with the singing on the historic recordings. The demise in vocal grandeur and the lack of mastership can almost instantly be heard.

IV.

As it was custom at the Metropolitan Opera since its inauguration in 1883 (with Faust, BTW), Act IV directly launches into the church scene, and in Act V, the Walpurgisnacht as well as the ballet are omitted. Also, there are minor cuts throughout the performance, mostly in repetitions of chorus scenes.

On this Saturday afternoon on 20 March 1937, Wilfred Pelletier, a Canadian conductor born in 1896, lead the performance. Pelletier was “the man in charge” for the French repertoire at the Metropolitan Opera from 1929 to 1950. His reading of Gounod’s score ist vital yet thoughtful. The small allargando he commands in the waltz scene sneaks in unnoticed at first. As does the organic accelerando when the chorus resumes the waltz melody. In the love duet that concludes Act III, Pelletier builds a climax and encourages Marguerite and Faust to mobilize all their vocal power before the music descends into the moving and soothing pianissimo chords over the falling curtain. The conductor’s rendering of Méphistophélès’ aria “Le veau d’or” fully displays his understanding of the score. He makes the orchestra available to Ezio Pinza’s devilish versatility and — for what it’s worth — the latter’s encompassing vocal command of his role.

V.

In the following summer of 1937, Ezio Pinza will sing Don Giovanni and Figaro at the Salzburg Festival under the baton of Bruno Walter. Here, on a Saturday afternoon in late March 1937, the bass is the driving force behind the drama: vocally funny in the scene with Ina Bourskaya’s Marthe Schwerlein, commanding Helen Olheim’s Siebel, thoroughly convincing in luring the old Faust into the deal. As always, Pinza succeeds by acting with his voice. With excellent command of his musical instrument, the Italian-born bass lets us feel Mephisto’s power even 80 years later.

VI.

Richard Bonelli, born George Richard Bunn in Port Byron, New York, sang Valentin. As few might know, Gounod always looked at that part as a comprimario role, “Écoute-moi bien” being the only solo concession to the baritone. Here, in the New York of 1937, Valentin’s cavatina from Act II, “Avant de quitter ces lieux”, has been included (as it is custom today). Bonelli gave a fine rendition, sang a well-knit line and did not let us hear any vocal difficulties; not even with the bariton’s high ‘g.’ Bonelli’s voice was of lighter timbre than that of his American colleagues Leonard Warren and Lawrence Tibbett. It also was of smaller calibre than the latter’s. However, Bonelli sang a fine performance, and one is no longer accustomed to singers of this sort.

VII.

The Marguerite of Helen Jepson did not only impress with an impeccable sung aria. Building on Wilfred Pelletier’s support, Jepson succeeded in making Marguerite’s inner conflict audible: The story of King Thulé on one handside, her personal situation on the other. If you ever wondered where Maria Callas’ insights1 with respect to Marguerite’s “Ah ! je ris” stemm from — look no further: Jepson only touches on the top ‘g♯’ after executing the opening trills with an effortlessness yet firmness unheard today. This impression stays for the following “Ah !” on the soprano top ‘a.’ The soprano lingered on the concluding top ‘b’ with a remarkable lightness, as if there were no more appointments today… It goes without saying that Jepson was able to round off the phrase with a nice concluding ‘e.’

Charles Gounod

»Faust«

Crooks · Jepson · Pinza · Bonelli

Metropolitan Opera

Wilfred Pelletier

Immortal Performances IPCD 1097-2

Remarks that Jepson’s Marguerite was not on the level of Crooks’ Faust and Pinza’s Méphistophélès might refer to the fact that the soprano’s voice bloomed mainly in the upper middle and the top range. However, one will not object to Jepson delivering most of her part with sustained legato, thus creating a flow and a forward movement one seldom comes to experience in today’s performances.

VIII.

On 20 March 1937, Faust was sung by the then 37 years old Richard Crooks. This lyric tenor had made his operatic debut ten years earlier as Cavaradossi at the Staatsoper Hamburg. After his return to the States, Crooks became one of the stars of the Metropolitan Opera. His lyric tenor voice was able to produce the most distinguished pianissimi and piani without having to resort to falsetto. By 1937, Crooks had developed a unique art in launching those soft top notes. Some seem to be almost core-less although all of them bear the required amount of chest voice.

If one wants to criticize anything, it may be Crooks’ leaning toward portamento whenever the voice ascends to the top. I don’t know about you, but I am more than happy to listen to some over-frequent use of (skillfully executed) portamento instead of having to endure singled-out top notes yelled in forte because of a tenor’s more substantial technical shortcomings. Just listen to the top ‘c’ in “Salut ! demure chaste e pure” and the descent that follows: This is vocal artistry at a level that has no equals today.

IX.

In the liner notes to the 1937 recording, IPRMS’s producer Richard Caniell writes about the challenges he had to overcome during the restoration process. Parts of the transmission discs obtained from NBC turned out to be 1.5 % sharp while parts of Act III changed from 5 % flat to up to 1.5 %. As one may imagine, making those kinds of corrections in addition to the overall restoration process is no little achievement. To make things worse, somebody had alrrady altered the dynamics, often putting the singers in the back after loud orchestral sequences. Caniell noted that on some occasions he had to add up to 10 decibels in order to restore the sonic balance.

Of course, there are still grits and ticks, some varying background nose and passages with rather muffled sound. Those who expect Dolby Digital sound will certainly be disappointed. Those however, who are interested in the history of great operatic singing will instantly recognize this treasure and a vocal artistry which, at least to my knowledge, remains unsurpassed until today.

- John Ardoin: “Callas at Juilliard. The Master Classes”. Amadeus Press, Portland, Oregon, 1998; ISBN 978-1-57467-042-4, 304 pages. ↵